Go Tell It To The Spartans

GH on a bank and its remarkable boss

You may never have heard of Rob Ferguson, who died aged 78 on Saturday night after a long illness, but few have been so influential in the world of Australian finance, as the long-time managing director of the trend-setting Bankers Trust Australia. In 1998, Rob recruited me as the bank’s official historian, which included hosting me on his farm as I wrote this book; twenty years on, I gave this speech about the organisation on the occasion of the presentation of fellowships honouring Rob’s late friend and colleague David Williams. If you're curious about how organisations work, this is where I learned the most about it.

Let me begin with a personal, cautionary tale, which came to mind yesterday as I arrived at the airport in Melbourne my standard hour before departure. Many in this room will remember Chris Caton, for twenty-five years the chief economist of BT, and a tremendous man of cricket with whom I exchanged many a ludicrously complex trivia question. One particular day we got to discussing travel, because I was off to the airport that afternoon and observed that I liked to be there in plenty of time. Chris tossed off this line – I still remember it. ‘You know what Milton Friedman said, Gideon? If you never miss a plane, you’re spending too long in departure lounges.’

That day I said my adieus in plenty of time. But I’m bound to say that Chris’s admonition preyed on me a little, and the next time I had a plane to Sydney to catch I approached the obtaining of a taxi to the airport in a fashion bordering on the blasé. You know what happens next don’t you? Much to my chagrin, I missed a plane the only time in my life, thereby learning an important lesson: ‘Never take travel advice from monetarists. Keynesians maybe; never monetarists.’

So there. My subject tonight is the legacy of BT, in honour of the man whose name adorns this excellent fellowship. It’s a weighty topic for an august company, that makes me a little queasy, because the ethos of BT in my experience of it was accented to living vividly in the present: the high-falutin had no place in the thinking of its founding generation, the long-term was next Tuesday. So, like a good journalist, I’m going to trivialise it – well, maybe not quite trivialise, but personalise it, albeit with good reason.

There is a sober, academic speech to be given here about BT’s pioneering in Australia of foreign exchange, swaps, options, promissory notes, $US Euronotes, semi-government paper, about its role in the privatising of Commonwealth Bank and Woolworths, about its virtual invention of retail funds management through the medium of investor roadshows, and eye-catching advertisements. You could stretch its works from the financial structuring of the first Chinese investment in overseas mineral resources, the Channar iron ore project, and the underwriting of Mel Gibson’s last appearance as Mad Max, 1985’s Beyond Thunderdome.

But I suspect BT is best considered in personal terms, the way it built, nurtured, altered and inflected lives – momentously when you consider its huge and diverse alumni, featuring names like Chris Corrigan, Rob Ferguson, Kerr Nielson, Jillian Broadbent, Olev Rahn and Ivan Ritossa. In many ways, BT remains in the headlines: Peter Warne chairs Macquarie Bank, Rohan Hedley is starting over with Hayberry Global, Richard Farleigh is securely ensconsed in BRW’s Rich List. It’s been said of investment banking that the assets go down in the lift every night. In BT’s case, many have kept going: these days you have Mike Crivelli as director of a Kings Cross charity, Bruce Hogan running an ethics NGO, Chris Selth in charge of an ethical investor, Rowan Ross chairing a fertility research group and Col Roden an indigenous women’s shelter. What brought together such a diverse bunch in the first place, and what did that place instil?

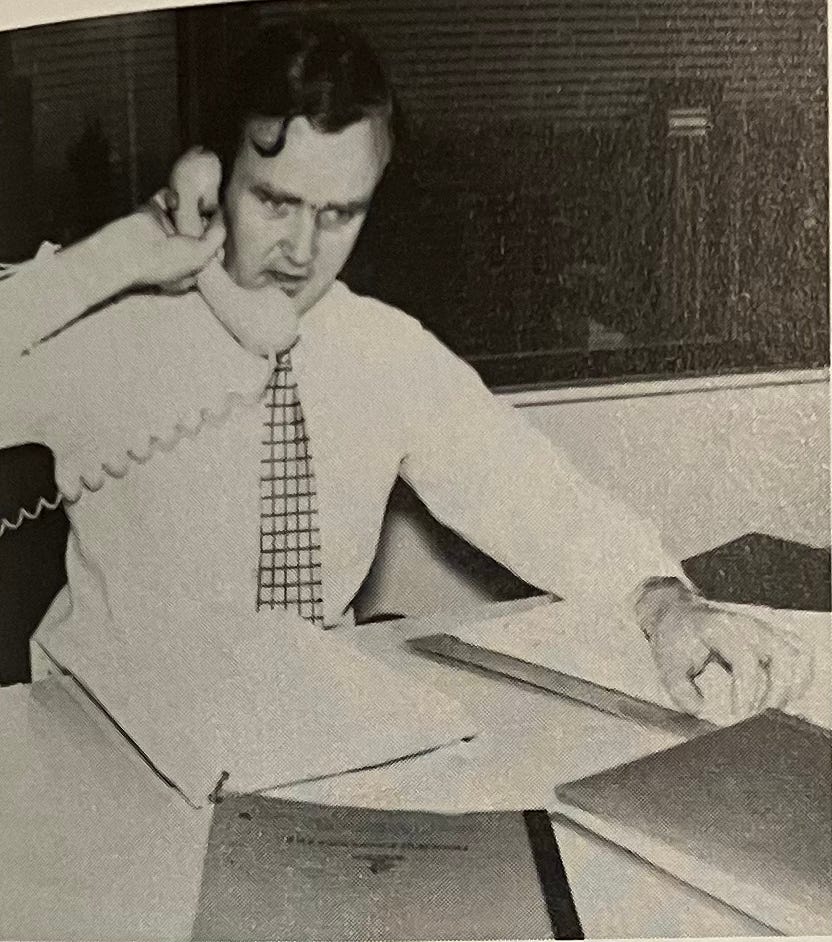

I may as well continue the personal perspective. I first spent time at BT Australia twenty-five years ago when I was working at The Australian, and the magazine asked me to recommend a financial institution as a subject. I chose BT because it was both highly successful and somewhat secretive: but Rob Ferguson and I had a mutual friend in Max Suich, which gained me entre for an instructive week in its halcyon days at Australia Square. Twenty-four years after posting a shingle as a minuscule foreign-owned merchant bank, BT Australia was the hottest name in Australian funds management, and a force to be reckoned with in trading and corporate finance. It had happened so quickly, in a generation, that the firm was simultaneously at the cutting edge of innovation while clinging superstitiously to their old premises and former ways: the dealing room was so packed that the windows fogged up from the inside; the atmosphere remained so homely that the tea ladies still circulated chocolate biscuits on trolleys on Fridays. Corrigan was around the corner by then, in a tiny office at Patrick Corporation. But his philosophies remained in widespread use at BT, where management was overhead, a dollar saved today was a dollar saved forever and you could pay the landlord or pay yourself. BT people were intense and driven, but also monastically austere: in a flamboyant and profligate age, they worked long hours, did not drink at lunchtimes, travelled up the back of the plane, scorned to fraternise with rivals, spent the organisation’s money like it was their own, and lived utterly in the present. Basic historical questions drew blank looks. If knowledge wasn’t going to make you a buck, what purpose did it serve? They reminded me a bit of Sherlock Holmes, who startles Dr Watson when they first meet by revealing he does not know that the earth rotates the sun: ‘Now that I do know it, I shall do my best to forget it….What the deuce is it to me….If we went around the moon it would not make a pennyworth of difference to me or my work.’

I remember Rob Ferguson saying at the end of that week how salutary the experience had been for him, realising how little he and his people knew about the history they had made, having been too busy making it. When at length I was retained to write a book, I grasped how big a step it was for an organisation to which introspection did not come naturally - which was precisely what made it worth doing. By this stage, BT had taken the scary step of leaving home, evacuating Australia Square for Chifley Square, more commodious but more ostentatious. It had occasioned more soul-searching, to which I was duly privy.

These days we talk up hill and down dale about organisational culture. In those days, not so much. BT had no motto or mission statement, no list of approved values, no sacred relics or totems. There was an hilariously eye-gashing tie which nobody would have been seen dead in; there was little interest in sponsorship or philanthropy; the logo was a dowdy inheritance from BTCo. Yet nobody I spoke to had any difficulty in explaining what the organisation stood for: that it was the low-cost producer; that it represented the new and fresh against the old and hidebound; that it hired people and offered freedom rather than filled jobs and designated tasks; that you saw what needed doing and just did it. When Paul Keating foreshadowed the issuing of foreign bank licences in the mid-1980s, for example, Bruce Hogan and his colleague Michael Cole presented a strong case for seeking one. Corrigan heard them out and said simply: ‘Well, if you think it’s so important, just go and bloody get it.’ Which they did. If you thought your boss was wrong, meanwhile, you told him. Kerr Neilsen now omnipotent reigns, but back in the day his opinion was one among many. One day, it is said, he presented a case for investment in the electronic giant Phillips. ‘It’s got great asset backing,’ he said. ‘So did the Titanic,’ responded his droll subordinate Chris Selth.

In retail funds management, BT did give thought to image. By doing spots of economic and business commentary on Good Morning Australia in the early 1980s, Mike Crivelli pioneered the genre. By commissioning John Bevins’ renowned long-copy advertisements in the mid-1990s, Terry Power and the late Sheenagh Stoke revolutionised the way financial services were promoted. But internally it developed few airs and no pretensions. One day, Chris Corrigan and Rob Ferguson interviewed a young upstart for a job, and were struck by his peppery, argumentative nature. ‘Jeez,’ said Corrigan. ‘He’s hard work.’ Rob nodded: ‘Yeah, but we’ve got to hire him. He’s so smart.’ Which is how Bruce Hogan joined.

To political correctness the firm was likewise a stranger. Its Christmas parties handed out a Rat Up a Drainpipe Award and a Teaser Award – the latter was an empty box. One of my favourite quotes was attributed to Michael Cole, when he issued redundancies at BT’s stockbroking arm: ‘If a couple of bodies get dropped on the tarmac, people know the terrorists are serious.’ BT exhibited a powerful disdain for outsiders, not simply competitors like the retail banks and life offices, but its own parent company, distant enough to be treated dismissively. A favourite Hogan story was told me by Col Roden, who described one day how a diktat came from BTCo chairman Charlie Sanford demanding groupwide layoffs. ‘Look at this piece of shit,’ said Bruce holding it up. ‘Know how I’m going deal with this?’ He threw it in the bin. No wonder, Sanford later told me, that he thought BT Australia less as a culture more as a cult.

Nor was there much interest in that other modern hang-up, work-life balance. Rob Ferguson, considered and humane, fought the good fight in this respect. Rob was a remarkable man, with an eclectic mind and an uncanny intuition. One day in the early 1970s, he returned from meeting a rising entrepreneur, Frank Lowy, and said that BT should liquidate its investments and bet everything on Westfield. Why? He sensed Lowy’s restlessness, the way his eyes darted round and his hands gestured. The developer could not wait to stop talking and start doing.

In the early days, Rob acted as counterweight to the mercurial Chris Corrigan, and could sometimes gave the impression of unwordliness. One year he received a million dollar bonus; a year later, company secretary Greg Goodman noticed it was untouched; in fact, Rob had forgotten about it. But in a place of strong egos, he had his well under control, could see past, over and round it. At BT’s annual conference in August 1996, he gave a famous speech entitled ‘You have permission’. In it he encouraged his people to do some of ‘the little things’ that made life worth living: ‘We buy your output not your time and I think we’ll get much more output and for longer, and you will be happier, if we concentrate less on time and on these cultural issues of being the last to turn off the lights.’ Many, of course, received this message sceptically – these were Spartans, not Athenians. Bruce Hogan had a sardonic jest: ‘Still married, are you? Obviously not working hard enough.’ By the time I was there, women comprised forty per cent of the workforce of BT, yet only the remarkable Jillian Broadbent had pushed through to the management committee. An equal opportunity aggressor, it squandered a good deal of female talent by its inflexibility.

At the same time, people talked about these things quite openly with me. That it was a great place; that it could also be a cruel place; that it offered massive freedom and responsibility; that it demanded absolute authority over one’s life; that it was all out in the open; that it was really all out in the open; views were put with utmost confidence and candour, exactly as I had hoped, as I would not have been interested in an institution that was just sitting for an official portrait. Partly in reciprocation, I decided it would be a BT history done the BT way. I worked extremely hard, as hard as I was able: 14-16 hour days as a routine. I produced a 200,000-word book involving more than 200 interviewees and hundreds of boxes of archival material in a year. I was offered a trip to the US to interview Sanford and a dozen other American executives involved with the company, but I passed it up, saying that I could do it on the phone – I was determined to be the low-cost producer myself. I would speak to everyone too, including the disaffected and jaundiced.

I remember ringing Bruce Hogan to cajole him into being interviewed. By that stage, of course, Bruce was gone - none too happily, having lost out in a power struggle with Rob. No-one was sure whether he would consent to be involved – some were very sceptical that ‘The Croc’, as he was nicknamed, would consent to being involved. I was advised to prepare for a ‘death roll’, which is how BT people described the experience of his questioning. They weren’t wrong. 'So….this project? What’s it all about it? But why? But why? Why do you say this? Why do you think that?’ Actually, I was totally up for this, because that he had not said no off the bat meant that he was curious. He interrogated me for a solid twenty minutes then said abruptly: ‘OK good, come see me tomorrow at 10am.’ When I arrived he spoke with absolute frankness and without regret, if a single flinch. One of the most fabled moments in BT history was in November 1993, when, like the Grinch who stole Christmas, Bruce did away with the institution of chocolate biscuits on Fridays, observing that catering costs had risen more than half in two years. Gossip columnists rejoiced in the furore that ensued. I ventured the subject of Tim Tams and Jaffa Cakes circumspectly. ‘I don’t find it amusing,’ he said. But he was honest about that too.

That was the spirit in which One of a Kind was readied for publication too. An editorial committee was convened by public affairs manager Stephen Mills, roping in two tribal elders: David Williams and his old mate Kevin O’Donnell. Time and again, a sensitivity would arise, a concern would be aired, and either David or Kevin would say: ‘Well, yes, but if we’re not to be honest, then what’s the point of this project?’ I can say hand on heart that One of a Kind is as close to uncompromising as a company history gets, because BT was as close to uncompromising as a company could be.

Let me interpolate a word here about David, who joined BT after a substantial career at Commonwealth Bank, ran BT’s Melbourne office, became its first human resources director, then its third chairman. David was actually not a cultist. He was oftentimes a gadfly. He disapproved of BT’s transaction focus, and its failure to nurture good relationships. He looked askance at Sydney’s penny-pinching ways, and insisted on fittings for Melbourne that were if not plush at least comfortable – Rob, instinctively frugal, used to call the Melbourne office the ‘Taj Mahal’ because it featured the scandalous excess of a coffee machine. David did not believe that management was overhead. When he took on HR responsibilities, he found it disturbing how many aspects of employee welfare BT had let slide over the years in its expectation of superhuman endurance, and tempered some of its extremities. He recognised the chocolate biscuit wars of 1993 as about more than Tim Tams, more even than costs, but evidence of how the working contract is sensitive to tiny indulgences – as he said to me, there’d have been less outcry had BT announced no salary increases for a year. I count myself fortunate to have known and worked with David because he was both immensely loyal to the organisation and a cogent critic of it – that’s a hard balance to strike, but David did, and in that sense his memory and example are very precious.

I started my remarks tonight with a trivial example of a throwaway remark that stayed with me. There’s an equivalent in the history of BT. It was uttered at a breakfast meeting at New York’s Hotel Pierre on 23 April 1985 to which Corrigan took Al Brittain III, Charlie Sanford’s predecessor at BTCo, to meet Paul Keating. For all their political differences, Corrigan enjoyed a curious simpatico with Australia’s treasurer: born two years apart, they were working class boys made good, Corrigan the son of an electrician, Keating of a boilermaker; both were impatient, insouciant, challengers of entrenched interests. It was two months since BT had been awarded their Australian banking licence, during which Corrigan had nursed a hope that Keating would make it a stipulation that the licensees issue local equity. Brittain raised the question with the treasurer, who waved it airily away: ‘Don’t worry about it.’

It was the beginning of the end of Corrigan – he was shortly to relocate offshore, and would have to go elsewhere to fulfil his hankering to be a principal rather than an agent. It meant, in the long-term, that BT would remain beholden to the fortunes of its parent, whose derivatives misadventures would spell the end of this first phase of its development thirteen years later.

Yet about that I would say this – that BT Australia in its first thirty years belied the common assumption about only equity binding employees to an organisation’s interests. BT people liked their money. As at every investment bank, bonus season was an annual frenzy. But its people identified with their firm for reasons wider and deeper – the perception that it was the best, the brightest, the toughest, the leanest, the meanest. As Steve Jobs said of Apple, it was more fun to be a pirate than to join the navy. I left my experience of BT, one of the most exhilarating projects of my long working life, a changed person, having learned that monetarists are untrustworthy travel advisers and far more. It’s quite possible that the organisation in its pomp was, as the title said, One of a Kind. But there remains, I think, much to learn from it, and to be inspired by. I commend the David Williams Fellowship as very much in its spirit.

While cricket touches on money. personality, power and culture - you hit your stride on a broader canvas. Finance as if people mattered - both inside the investment decisions and in the assets being transacted. Money printing and the financialisation of everything means that today's version would be "My Interview with an Algorithm". CEO's loom larger because like Treasurers they are the only personal identity to vast systems neither they or their clients understand. There is a cyclicality to these things that will make your BT book an MBA text again in 20 years time.

I was a recruiter of temporary accounting staff in Sydney during the 1990s and BT was my #1 client. My temps loved their assignments at BT, and many of them were converted to permanent staff over the years. The BT hiring managers I provided temps for were inevitably intelligent, hardworking, skillful and respectful. As an inexperienced 26-year-old agency recruiter with no banking background, these hiring managers could have made my life difficult, but they never did. The example Rob Ferguson set was unmistakable throughout the company.