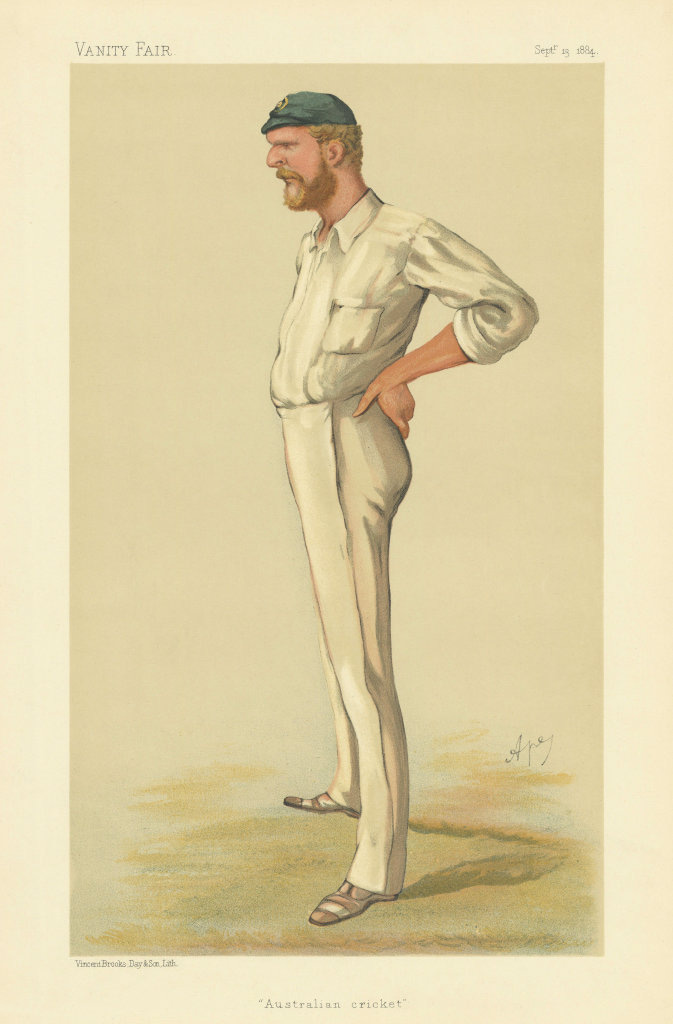

In August 1884, Vanity Fair, the plushest periodical of Victorian England, was casting around for a character for the honour of caricature on its weekly Men of the Day page - a cavalcade of leading figures from politics, culture and the arts captured in characteristic attitude by its great cartoonist ‘Ape’ (the Capua-born exotic Carlo Pellegrini. In more than 300 previous instalments, the magazine had only thrice turned to cricket - publishing portraits of WG Grace, Lord Harris and Frederick Spofforth. Now, to incarnate ‘Australian Cricket’, ‘Ape’ immortalised George John Bonnor, in profile, brow furrowed, arms akimbo, a lean and angular proclamation of colonial intent.

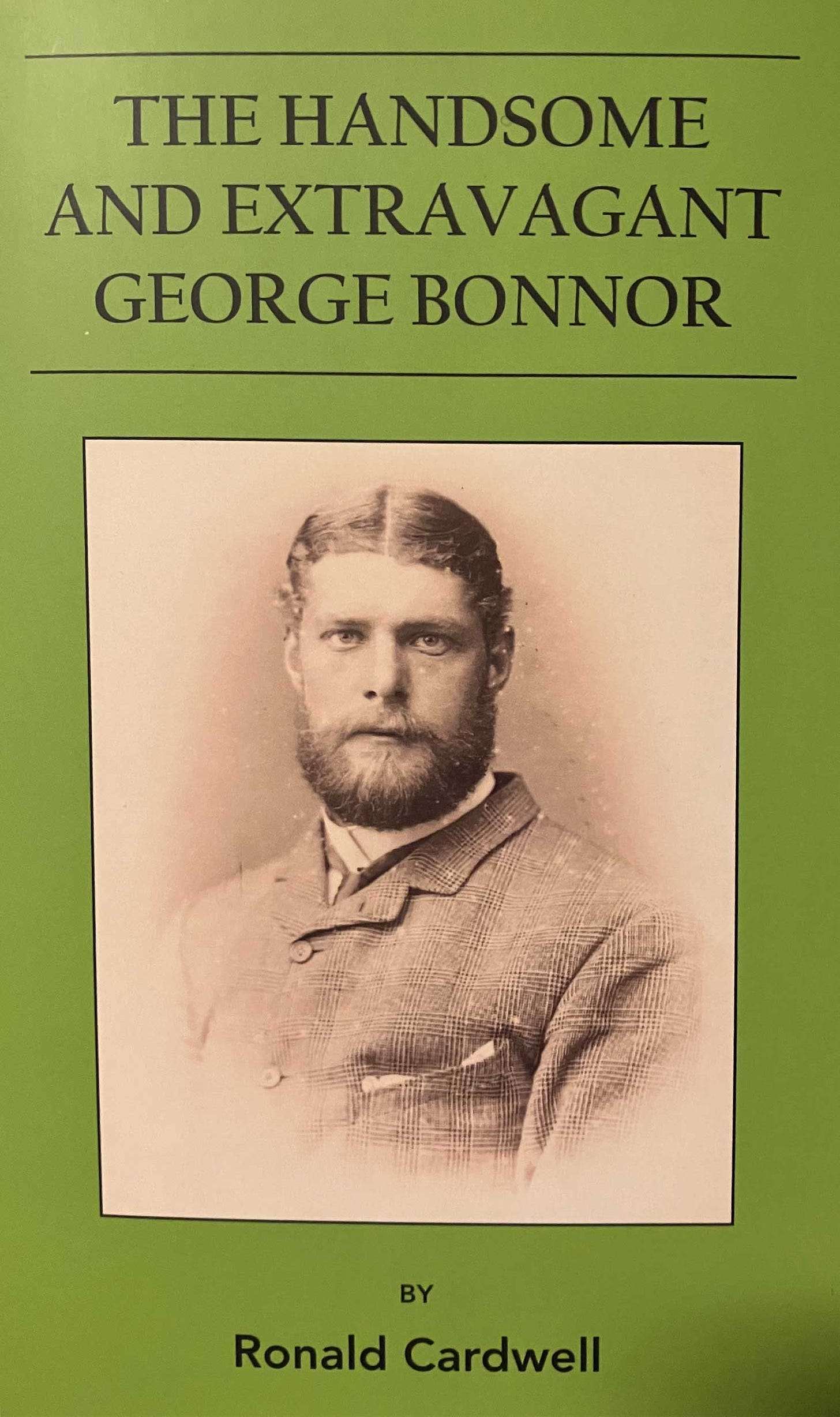

On the face of it, the honour was hardly earned: Bonnor was coming off scores of 25, 4 and 8 in the series. Nor did his subsequent career record register great improvement. After his solitary Test century, at Adelaide Oval in March 1885, he faded out with ten consecutive single figure scores. For all his reputation as a hitter, his Test and first-class records now seem disarmingly modest. So why Bonnor? Because, with his blue eyes, flaxen hair, tawny beard, towering height and perfect proportions, he looked magnificent. Perhaps no cricketer in history has been so rhapsodised for their physicality, and continues to be so - for the title of an attractive new monograph by Ronald Cardwell is The Handsome and Extravagant George Bonnor.

Bonnor’s height is variously listed as somewhere between 193cm and 198cm. On the authority of The Referee, Cardwell tells us: ‘By 16 years of age he was six feet five and a half inches [1.96m] and weighed in at sixteen stone [101.6kg]’. Vanity Fair described him as a ‘quiet, amiable, low-voiced, comely giant, standing six feet six [198cm] in his boots, measuring forty-five inches around the chest, and weighing seventeen stone all but two pounds.’ That would make Bonnor as tall as Cameron Green, and considerably taller than the average male height of his era of about 170cm. What’s more, he was a perfect physical specimen. AA Thomson said: ‘Despite his enormous height, his proportions were so near to perfection that he was incapable of a clumsy movement…..For so big a man, he was active as a cat and a remarkable sprinter’. JC Davis said:

George was a physical wonder. He stood 6 feet 4 inches high, was symmetrical in his superb physical proportions, and carried himself with regal gait. He wore a neat-trimmed beard of golden chestnut, was garbed perfectly, and, in my mind's eye, remains the handsomest figure I can recall having ever seen in cricket. One was very young when Bonnor's giant figure adorned the cricket field. Though so tall, he moved over the outfield with swift, easy, athletic grace, and must have been one of the fastest that ever intercepted the little red ball out in the “country." "Beauteous George" is how an old cricketing friend always referred to "Bon."

To be fair, Bonnor could be a formidable opponent. His 128 in Adelaide involved the first century in a session in Test history, and his 267 for Bathurst against Orientals included ‘some of the finest hits ever seen on any cricket ground in the universe’; he reputedly threw a ball 110m without taking his coat off and hit a ball from Orange to Bourke. But his stature, that the critic John Ruskin likened to a ‘Greek God’ and the belletrist EV Lucas to ‘a god from another planet’, was reinforced by a larger-than-life character. Green sometimes looks a little embarrassed by his specifications, in unending fear of a too-low doorway - perhaps no cricketer so enormous has ever had such a small personality. Bonnor was notorious for his good-humouredly expansive self-opinion. He once opined that there were three great cricketers: ‘Well there’s WG Grace, there’s Billy Murdoch and it’s not for me say who the other is.’ He later opined that there were two, causing his interlocutor to remark: ‘Who’s the other, Bonnor?’ Fifteen years after his death, a memoirist still spoke fondly of his boasts:

According to the mighty smiter, he was the best boxer, best runner, best footballer, biggest hitter the best singer, and the longest cricket ball thrower ever born in New South Wales. 'I was the fastest bowler that ever lived,' he said, 'and so great was my pace that in a match at Orange after sending down one of my fastest deliveries which I knew would be snicked in the slips, as I bowled for it, I ran down the pitch, chased the ball after it had been played, and caught it at deep-first slip.’

My favourite Bonnor story - for some reason it appears to have eluded Cardwell - concerns his being feted in London in the 1880s by the Johnson Club, the gentleman’s dining club devoted to the legacy of The Great Cham. In an 1898 essay, club member Augustine Birrell described Bonnor being entirely bemused by the honour. The Australian said he had never heard of Dr Johnson ‘and what is more I come from a great country where you might ride a horse sixty miles a day for three months and never meet anybody who had.’ But, he added graciously, on the basis of the stories retailed at the club, he believed he would, like to have been Dr Johnson had he not been ‘Bonnor the cricketer’. Although men revelled in resembling him and governors wished to shake his hand , Bonnor basked most readily in female approbation. He was Murdoch’s best man. Asked by a lady admirer what the letters ‘LBW’ stood for after his name in the newspaper, he replied: ‘Loved By Women.’ Cardwell has a few candidates, even if the great man died unwed, and maybe like his dissolute father a bit inebriated. Bonnor, we learn, shared the family home in Orange with his teetotal brother James, who would apparently confine him to the stables when he returned worse for wear. ‘There are 39 stick figures carved into the stable door still today,’ reports Cardwell, ‘recording the number of times he spent the night in the stables.’ Verily are there statistics for everything….

Yet statistics have seldom been a meaner measure of a cricketer than in Bonnor’s case. Cricket then had a very different visual economy from ours, defined by distance and space. The spectator of Bonnor’s era needed a fine tuning to tell one cricketer from another - no wonder they fastened on a figure so instantly recognisable, so unique, so optimistically representative of colonial possibility and virility. Imagine the stupidity of putting a number on his back. On Bonnor’s death in 1912, Wisden editor Sydney Pardon fancied that English cricket fans still saw him in imagination:

Few cricketers of his generation are so

vividly remembered. He was last seen on an

English cricket field in the season of 1888, but

people who saw him play in those now rather

far-off days never cease to talk about him. He

was not a man to be readily forgotten, his mere

presence making him the most striking figure

in any company in which he found himself.

His countrymen? ‘The Late George Bonnor: The Colossal Batsman of the City of the Plains’ appeared in a concurrent edition of the Sydney Sportsman, the anonymous author of waxing Homeric of his presence one last time.

George Bonnor dead! a cricketer of yore —

Whose mighty hitting long the record

held;

A giant truly, towering sir feet four,

Whose famous batting still stands unexcelled!

He so delighted all the cricket crowds,

And sent the ball careering through the

clouds.And when the English bowlers he would face,

Out ‘in the country' they would place

their field,

For ‘dear old George’ they knew, would

make the pace;

Prodigious was the power which he revealed.

And marvellously too, the bail he'd time.

(Those were the days when Grace was in

his prime).

Bat, not alone in batting was he skilled,

George Bonnor every point knew of the

game.

Of stature tall, and yet of perfect build,

From him, the runs, they 'just like water'

came:

The 'young idea' Bonnor well could teach,

With eye unerring, and with mighty reach.At home, in England, on the cricket grounds.

The populace at Bonnor, how 'twould

roar,

For their enthusiasm knew no bounds,

When George was piling up a mammoth

score.

Jessop and Lyons both could belt the ball,

But Bonnor was 'the daddy of 'em all.’George Bonnor, as an ‘outfield', had no

peer,

Could throw the ball the longest distance

thrown;

A nerve of iron! (Bonnor knew no fear),

As he so often hath in England shown.

Than 'Handsome George’, no finer player

seen,

Australia long will keep his memory green.And what a star was he on English swards!

A subtle bowler 'twas who'd George deceive,

The ball he one time lifted out of Lord’s!

There with his play woe little 'make believe.'

Always in earnest, he would nothing shirk.

And roars of thunder greeted Bonnor's work.Australia in its heart a corner keeps,

For poor George Bonnor (who at Orange

died),

The famous batsman, with his mighty

sweeps,

The cream of English bowling he defied—

Then where can we on such another call?

He was the noblest Roman of them all.

‘Cameron Green: The Colossal All-Rounder of the City of Money’? Yeah nah….

Sounds like he was the Muhammad Ali of his day.

Bonnor's name lives on in the now T20 Competition run by the Orange District Cricket Association and played for by teams from Orange & Bathurst. Current Thunder Captain Phoebe Litchfield played in this competition as a teenager against the men and managed a top score of 38 not out.