Gideon Haigh

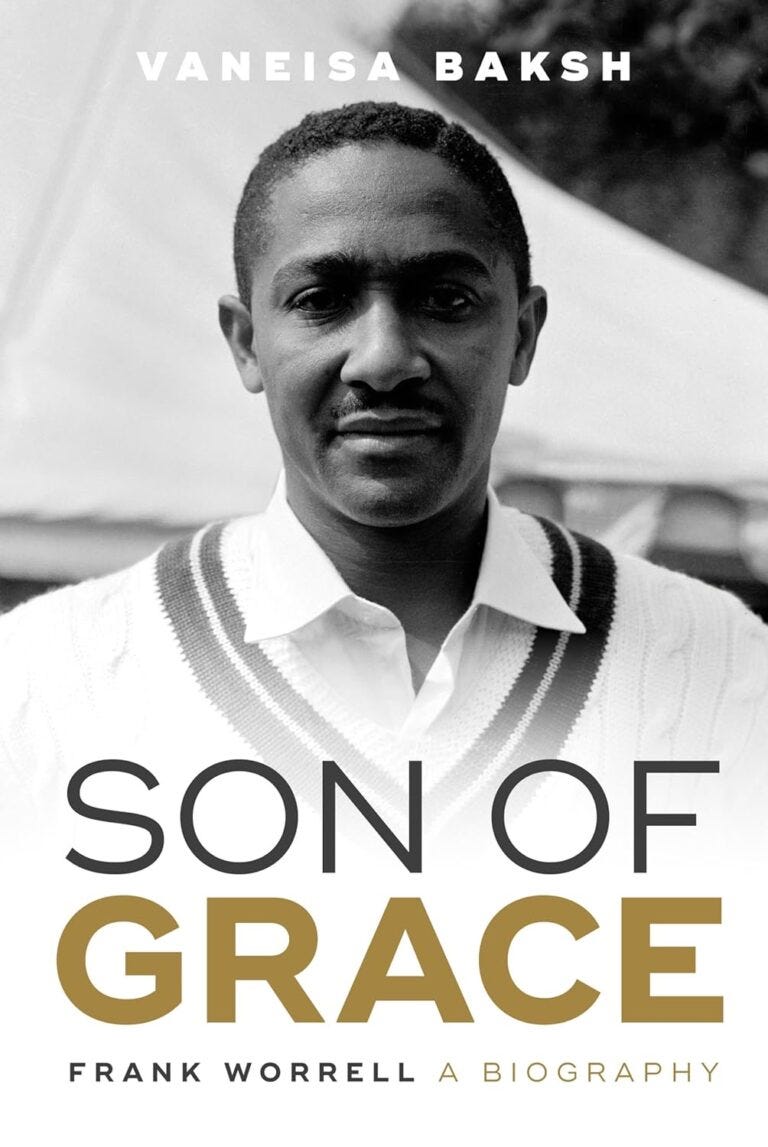

The photograph on the cover of Vaneisa Baksh’s new centenary life of Sir Frank Worrell, Son of Grace, was taken in 1963, early on the West Indian captain’s final tour in England. It is at first glance a nondescript image: the expressionless Worrell is giving the camera a perfunctory glance, resting captain face. But in comparing it to a photograph taken more than a decade earlier, Baksh pores over its lineaments:

A press photograph taken in May….shows him staring serenely somewhere into a distance, the left eye slightly off-centre. The ears are less obtrusive because his face has grown outward and gathered them in. The hair is still cut low, neatly edged, and is now parted on the left - the parting had been fashionably shifting over the years. The moustache has responded to assiduous grooming and has become one of his defining features for its impeccable symmetry; marking a peak that begins precisely under the tip of his nose and extends outs at an angle of 160 degree precisely to the tips of his lips.

So, sensitively, on - and Baksh is right. The longer you look, the greater the temptation to read the subject, precisely because it gives so little up. Baksh tells us that that summer in England, Worrell was such a ‘celebrity’ that his likeness went on show at Madam Tussauds. This photograph could be of that waxwork. It is, at the least, a mask, smooth and inscrutable. Worrell’s team was replete with outsize personalities: Sobers, Hall, Griffith, Kanhai, Hunte, Gibbs. It was almost like Worrell, in all his enigmatic suavity, adopted a proportionally sunken profile.

Sixty years on, Worrell is mainly a name, and sometimes barely that - Brendon Julian’s mispronunciation of the Frank Worrell Trophy a year ago remains fresh in memory. And where the trophy once virtually conferred number one Test status, today it resembles the kind of cricket bric-a-brac you might give at your club for first division bowling averages. Still, as the first non-white cricketer knighted, Worrell casts a shadow that’s hard to sidestep, even if it is vague in definition.

Baksh begins her book by juxtaposing two 1963 interviews of Worrell by respected English media figures: the broadcaster Rex Alston and the columnist Ian Wooldridge. To Alston he turned his coolly detached side, calling himself ‘a fatalist….drifting in the breeze’, stressing his Anglophilia and conflict aversion. To Wooldridge, however, he showed a glint of his steel, recollecting that much of his career had been in conflict with West Indian cricket authorities, that he ’had a hell of a chip on his shoulder’ and had been ‘fighting all sorts of issues, both actual and imaginary’. Reconciling the personas isn’t impossible: fighting can lead to fatalism, after all. Still, this is hardly the only tension in the life to be reckoned with: he was a free spirit and a freemason; he was the pioneering black captain of West Indies with a white grandfather, who also lived much of his life in England; he was an enemy of prejudice who seriously considered captaining a team to apartheid South Africa; he was a skipper who said after Nari Contractor’s near-fatal head injury in 1961 that he would never lead Charlie Griffith into the field again yet did so two years later against England.

The emollience of that exterior, furthermore, jibes with two habits on which Baksh spends a good deal of ink: alcohol and infidelity. Worrell was both a mercilessly hard drinker and a compulsive philanderer, which slowly hollowed out his relationship with Velda, whom he married in 1948, ‘though they did not betray the myth of a happy marriage in public’. Worrell’s father had been a similarly hard dog to keep on the porch, while Velda had previously had an ex-nuptial child to an unknown man, which may have been part of the dynamic. Alas, Baksh goes no further. We learn no details of Worrell’s ‘numerous dalliances’, nor does Baksh speculate about what they may tell us of his personality.

In other areas, Baksh is extremely conscientious. We learn of the first attempt to install Worrell as captain of the West Indies, in 1954, which came up against the conservatism of the white plantocracy at the West Indies’ board, though by 1959 the celebrated campaign of CLR James to promote him in the pages of Trinidad's The Nation may have been pushing at an open door: Gerry Alexander was only too happy to give way, and the available internal records suggest little debate. What’s most interesting - timely, in fact - is Baksh’s exploration of the simultaneous initiative to have Worrell lead a private team of black West Indians to South Africa at the invitation of the non-white South African Cricket Board of Control. The retrospective belief in the efficacy of the sporting boycott on the end of apartheid is now so deep we have forgotten that there were alternatives, and that opinion only grew monolithic later.

Surprisingly, perhaps, the Nationalist government in Pretoria was not opposed. SACBOC’s invitation was instead decried by the likes of Nelson Mandela and Dennis Brutus, and also by Lord Constantine (‘Would it help them [black South Africans] in their battle to defeat apartheid? My answer is…an unequivocal no’) and Jackie Grant (the tour ‘will not quicken but delay the breaking down the barriers which are so part and parcel of the present policy’). But it was strongly supported by James:

They [the tour’s critics] are dominated by opposition to the South African government and apartheid. That struggle they want to keep pure. They are holding high a banner of principle. This means more to them than the struggle of living people…Think of what it will mean to the African masses, their pride, their joy, their contact with the outside world, and their anger at this first proof before the whole world of the shameful suppression to which they are subjected.

Plans for the tour advanced so far that blazers were tailored and logos devised, and it was, Baksh says, ‘not aborted because Worrell changed his mind about going; the pressure in South Africa became too much for the organisers and they backed away.’ What would have happened had the team toured? For apartheid could hardly have lasted longer than another thirty-odd years. This interests me because the sporting boycott of South Africa was freely invoked in November 2021 when Australia pulled the plug on its Test match against Afghanistan: we heard about how going ahead would give aid and comfort to the horrid Taliban, and that a ban would bring joy to the country’s benighted women. But this was always more about our feelings than anyone else’s. ‘Cancelling’ Afghanistan was cost-free virtuous posturing without measurable impact. The popular urge to ban, to exile, to anathematise is understandable and even popular; but it is often an excuse for not thinking.

James was, of course, far from always right. Baksh tells us that around the time he published Beyond a Boundary, James composed a 10,000-word essay about why he was ‘absolutely and militantly opposed to Frank Worrell being made captain of the 1963 team to England’, on grounds he was too old, and would mar his legacy by overstaying his welcome. The essay remained unpublished and probably just as well, as West Indies’ overwhelming victory provided a capstone on Worrell’s captaincy. It showed a streak of ruthlessness: having famously donated his blood to help save Contractor in 1961, he tolerated Griffith’s manifestly unfair action and wrung from him match-winning performances.

Son of Grace has its limitations. I understand Baksh’s aversion to recapitulating match descriptions, but her retelling of the fabled 1960-61 West Indian tour of Australia is strangely uninvolving. I was surprised not to find more about the tension between building a Caribbean cricket identity and the separate pushes for independence of the islands of the West Indies. My profoundest criticism is perhaps my least fair: that the book is too late; that undertaken twenty years earlier, when there were many more contemporaries of Worrell’s to talk to, it would have been far richer. Twenty years on, the legacies of that halcyon period of West Indian cricket have never been sadder or sorrier.

There is a further dimension to that cover photograph worth noting. Though none sense so, this is also the face of a sick man: within four years Worrell will be dead of leukaemia, aged forty-two. Baksh ably teases out the pathos. We learn of a New Year’s party at the home of Dattu Phadkar to ring in 1967, where a gathering in the kitchen was disturbed by their daughter: ‘I heard my mother say, “Pray, Frank, pray…” And then she saw me and fell silent.’ We learn that two suits Worrell had ordered arrived the day of his death: one served as his coffin attire, the other was returned to the tailor for a refund. And here, perhaps, lies another counterfactual. How different might West Indian cricket have been had Worrell, personality and a symbol, continued in its service? At the very least, we might have understood a little better who he was and what he stood for.

I think what has always most drawn me to your writing, is your implacable determination to speak the truth. As you reference above, it’s increasingly uncommon.

“Cancelling’ Afghanistan was cost-free virtuous posturing without measurable impact. The popular urge to ban, to exile, to anathematise is understandable and even popular; but it is often an excuse for not thinking.”

Right glad you keep thinking (& writing).