The Man Who Bought Bradman

GH on the commerce of a legend

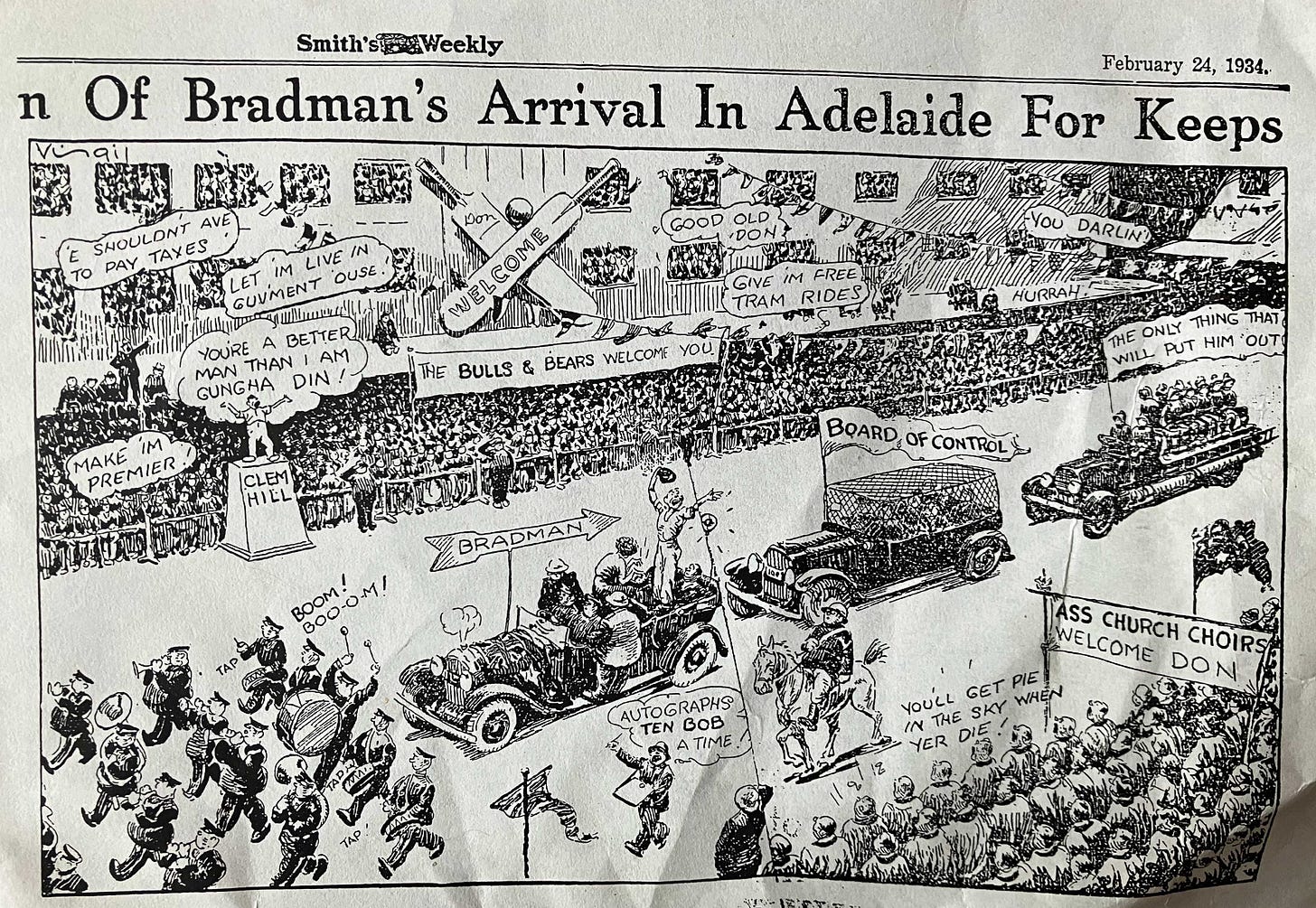

At 8.15am on Tuesday 13 March 1934, the Melbourne express to Adelaide made an unscheduled stop at Mount Lofty railway station. The platform was deserted as a well-dressed young couple calling themselves the Lindsays got off. A day continuing the recent heat wave was in the offing; the couple were grateful for the comfortable motor car that conveyed them to Adelaide’s plush Kensington Gardens. And so, inconspicuously, was Australian sport tilted on its axis, for the unassuming figure was Donald Bradman, with his wife Jessie. As the Women’s Weekly put it: ‘Adelaide is hundreds of miles and many hours from Sydney. There used to be a saying that it was only three 'ours' distance: "Our Harbor, Our Bridge, Our Don.” Now one “our” has gone.’

None of this, however, occurred of its own accord. And at last, John Davis has furnished a short life of the engineer of arguably Australian sport’s greatest coup, Henry Warburton Hodgetts Jnr. The deal had been foreshadowed a month earlier.

It was for Hodgetts’s plush Park Road home, Lichfield, that the Bradmans were bound that day ninety years ago; it was for Hodgetts’s club Kensington that he intended to play; it was for Hodgetts’s eponymous stockbroking firm that Bradman was planning to work after completing the forthcoming Ashes tour. As he explained:

Throughout the past few years I have lived cricket. I have been connected with sports goods, journalism, where I had to write cricket, and broadcasting, where I had to talk cricket. From morning to evening I had no chance of getting away from the game. It had become not a sport, but my life. Now, with business interests not concerned with the game, I can devote my spare time to cricket, and when I am away from the field I need not worry unduly about the game.

It turned out that there was plenty of worry in stockbroking too, but that was a decade hence. In the meantime, Bradman was the toast of Adelaide, and Hodgetts the toast of the South Australian Cricket Association, with which this most lively and clubbable of men had been associated almost four decades already - since his first administrative role, as a sixteen-year-old assistant secretary of East Torrens CC, he had been conspicuous and increasingly flamboyant local sporting personality.

In addition to Bradman, Hodgetts had been simultaneously and successfully courting perhaps Australia’s choicest young batting talent, Tasmanian Jack Badcock. The pay off was huge: in their first four seasons in Adelaide, the state twice won the Sheffield Shield and twice finished second.

Then, alas, it all went wrong. In Bradman’s Farewell to Cricket, he accords to his old friend the merest mention, and only in the context of the relocation: ‘At this time…an offer was made by Mr HW Hodgetts, a member of the Board of Control, who had his own sharebroking business in Adelaide. He invited me to join his staff on my return from England.’ And, errr, that’s it. Yet it’s possible that only Jardine and Larwood, in different contexts, had greater impact on the Don’s life and career.

*

John Davis taught history at Adelaide’s Pembroke School, and has written its history, and that of its antecedents, King’s and Girton. It was while involved in these that in 1989 he chanced on the forgotten name of Hodgetts, for amongst the man’s many public roles was the chairmanship of Girton for almost two decades: his two daughters were students, while his three sons attended Hodgetts’s own alma mater of St Peter’s. As a native of Adelaide, Davis is sensitive to that city’s subtle gradations of class. Hodgetts was not of the purple. He was a telegraphist’s son, who came to stockbroking via a cadetship with the Post-Master General’s Office and the secretaryship of the stock exchange; an admirer paid his school fees; he was probably only able to buy his seat on the exchange as the result of contracting his advantageous marriage to Edith Gwynne, granddaughter of EC, and part of the far-flung and well-connected Mortlock family. He became not only a fixture of the local sporting community but a pillar of the Church of England, ‘always fluttering a 10/-1 note into the velvet collection bag, while lesser mortals covertly dropped in 1/- or the off threepence’ at St Edward the Confessor Anglican Church. Davis evokes his social milieu with such cameos as these:

During a Church of England Congress in October 1928, Governor Sir Alexander Hore-Ruthven invited Lieutenant-Governor Sir George Murray, Premier Richard Butler, Lord Mayor Lavington Bonython and a host of Anglican prelates and priests to lunch at Government House. As well as Bishop Nutter Thomas, the bishops of Ballarat, Carpentaria, Goulburn, Newcastle, Riverina and Wangaratta were guests. There were two deans, five archdeacons, four canons, twelve ministers and three laymen, one of whom was the Governor’s stockbroker, Henry Warburton Hodgetts Jnr.

Hore-Ruthven, later the governor-general Lord Gowrie, was a fixture on a gilt-edged client list that was a remarkable achievement for one of relatively plain origins. One wonders, in fact, whether Hodgetts’s instinctive kinship with Bradman was that of one arriviste for another. Both were confident in their respective fields. Both were self-motivated and self-made. They knew the value of a pound and the weight of a run.

Davis might have given us more on Hodgetts the sports administrator. Hodgetts attended his first meeting of the Australian Board of Control for International Cricket in January 1927, and was involved in many of its key decisions over the next fifteen years: he proposed that Australia issue the West Indies their first invitation to tour; he was among those who penalised Bradman for the cricketer’s breach of his first Ashes tour contract, albeit that he pushed for a lesser levy on Bradman’s ‘good behaviour’ bonus; he was one of the delegates who devised the first astringent telegram to the Marylebone Cricket Club complaining that Bodyline jeopardised ‘friendly relations existing between Australia and England’. Davis omits that Bradman’s openness to offers arose partly because of the failure in September 1933 of his co-venture with the sporting good manufacturer F. J. Palmer: only a quarter of the shares offered in the prospectus of Don Bradman Ltd were taken up after which, as his friend Johnnie Moyes recalled, Bradman ‘did not know what he would do’.

Three months later, on arriving in Adelaide to play a Sheffield Shield match, Bradman met Hodgetts and three colleagues on the SACA ground and finance committee, who afterwards minuted ‘that this association would be justified in endeavouring to secure Bradman’s services, and to achieve that objective to substantially subsidise any remuneration he could otherwise obtain.’ Three weeks later, Hodgetts went to Launceston to dangle a similar subsidised offer before Badcock. Reflecting their different statuses and aspirations, the SACA paid £500 of Bradman’s £700 salary at HW Hodgetts & Co and £169 of Badcock’s £338 salary at Browns Furniture Warehouse.

Davis quotes the academics Tom Heenan and David Dunstan, strenuous threshers of Sir Donald Strawman, decrying Bradman’s deal as shady shamateurism: ‘According to myth, Bradman joined Hodgetts to learn the stockbroking game. In reality, Bradman’s job was cricket.’ But surely, it could have been both. Bradman’s was not a pretend job or a feigned interest. Bradman’s co-author William Pollock observed of him: ‘The thing that most interests Don Bradman in life is work in business. He is methodical, he has a mind for figures, he is keen on making money. He may never be a very rich man, but I feel sure he will never be a very poor one. His head is screwed on the right way. He is a clever little devil – and I mean that affectionately.’ Bradman had not been able to get off the ground as a principal; perhaps being an intermediary was a more sensible option.

Davis puzzlingly excludes the on-going relations between Bradman and Hodgetts arising because of the latter’s continued involvement with the South Australian Cricket Association and Australian Board. Hodgetts was part of the push that made Bradman an Australian selector, then South Australian and Australian captain. When Bradman withdrew from the Australian tour of South Africa in 1935-36 in order to convalesce further from the appendicitis which had disrupted his 1934 Ashes tour, it was Hodgetts who at a farewell function described the captaincy of South Australia’s Victor Richardson as ‘representing a fitting tribute at the end of his career’.

‘End of his career!’ thundered Clem Hill. ‘Bunkum!’

But it was: there’s little doubting that Hodgetts was instrumental in ushering Richardson into retirement when he returned home so that Bradman could captain both state and country. Hodgetts was also one of the four Board members part of uneasy ‘hearing’ in January 1937 when Stan McCabe, Bill O’Reilly, Leo O’Brien and Chuck Fleetwood-Smith were accused of ‘undermining the authority of the captain’. Bradman always disclaimed responsibility for this arraignment, but the involvement of his employer was hardly calculated to disarm his colleagues’ suspicions. No captain had a stauncher administrative friend than Bradman had in Hodgetts; no grandfather had a grandson with a sharper memory than Richardson had in Ian Chappell.

All of which makes Bradman’s later distancing himself from Hodgetts the more poignant. Here is the fall of HW Hodgetts as narrated in Farewell to Cricket: ‘For me personally there suddenly came disaster. overnight the firm by which I was employed went bankrupt. In the midst of a long struggle to regain my health, and through no fault of my own, I became the victim of another’s misfortune. there was no time for reflection. I had to make an immediate decision as affecting my whole life.’ It is all very vague and discreet. So Davis offers, very valuably, a thorough account of Hodgetts’s fall - and Bradman’s corresponding rise.

In March 1929, Hodgetts’s Broken Hill agent Allan Hall committed suicide after it was discovered he had been making free with shares bought on clients’ behalf, using them as security for personal loans. Hodgetts was on the hook for Hall’s defalcations, and paid a heavy price. This does not, however, appear to been the chief cause of his subsequent problems; it was, rather, that Hodgetts fell into the same habit. Over the next decade or so, Davis reports, Hodgetts ‘used for security on cash advances almost every negotiable share held in his office’, digging himself a hole that deepened to almost £83,000. This was aggravated by misadventures in wheat futures and the bombing of Darwin, where he had been part of a syndicate to redevelop two hotels. ‘Hodgett’s only hope lay with an economic boom that would allow him to retire clients’ funds without anyone being the wiser,’ says Davis, ‘but boom years were impossible during World War II and its end came too late for Hodgetts to trade legally out of his dilemma.’

Some felt that Bradman must have known about the financial predicament that caused Hodgetts’s bankruptcy in June 1945, and his sentencing for ‘false pretences and fraudulent conversion’ - in fact, this is hard to reconcile with the fact that Bradman, who by then had his own exchange seat, was one of Hodgett’s two hundred and thirty-eight unsecured creditors, owed £762. What many felt, and not without reason, was that Bradman took advantage of Hodgetts’s disarray by gaining the Adelaide Stock Exchange’s approval to set up his own business on the same premises with the same client list in the same week - a pretty nimble act of opportunism in any terms, after which he put a lot of blue water between himself and his mentor. Bradman had just finished his last Lord’s Test when Hodgetts was released from jail. It’s unclear they met again before Hodgetts died the following year.

‘The stock exchange was keen to limit damage to its reputation and standing in business circles,’ Davis notes, ‘but what appeared to be its favoured treatment of Bradman raised eyebrows and questions.’ They were re-raised in November 2001, six months after Bradman’s death, when The Australian’s David Nason explored the interlude in ‘The Don We Never Knew’. Whatever the case, the Hodgetts we never even knew of is long overdue recognition. For the best deal that this ebullient, gregarious, somewhat overconfident man ever brokered stood the test of time.

Ian Chappell can certainly hold a grudge. I somewhat admire him for his persistence.

Excellent article, Gideon.

I've always thought that Bradman was, as you say, a bit of an opportunist regarding his takeover of Hodgett's business, but I've not read anything which would ping him with evidence as a shonk. Heenan, Dunstan, Nason, etc have been able to weave entertaining yarns about Bradman's alleged shortcomings, but their critiques have never found much purchase in the court of public opinion, including the accusation Bradman was (if I recall correctly) autistic and that the Don was an FTB. When all is said and done though, most people assume he's just another sportsman who leveraged his ability with bat and ball into a career in business, and I suspect his "threshers" want to take Bradman down a peg because Howard took him up a peg.